Annaleen Louwes Back From New York

Stichting Beautiful Distress

An interview with the photographer, Annaleen Louwes who spent almost three months as an artist in residence in Kings County Hospital Center in Brooklyn, New York at the invitation from Beautiful Distress. Now back in Amsterdam she is exploring how she will present the work she made there and share her reflections about the experience.

By Sjifra Herschberg

Picture: Annaleen Louwes

“I’ve been back now almost four weeks, but I still don’t have the feeling I have returned. I just haven’t been able to find my equilibrium. The first week I didn’t do anything, caught up on sleep. The second week went by in a flash. After that there was a job to do so I had to act as if I was back in my old routine. But only now, after a month is New York coming back to me and I have the feeling I can do something with it.”

Speaking is Annaleen Louwes who through the invitation from Beautiful Distress spent almost three months as an artist in residence at the Brooklyn Psychiatric Hospital in New York. At home now in Amsterdam, The Netherlands she is working through her experience to bring form to her work and her reflections.

“A bit like Annaleen goes in, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The reality was very different.”

“I left Amsterdam with a bit of a romanticized view of an American psychiatric hospital. A bit like Annaleen goes in, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The reality was very different. To begin with the hospital dealt mainly with outpatient care, similar to the Mentrum Psychiatric Clinic in Amsterdam rather than being an institution, although there was a department for so-called inpatients. That required me to change my point of view. Furthermore, the first week I was busy resolving practical problems. There was a room prepared where I could live and work, but there was no internet. My room was situated internally in one of the older buildings of the complex, which is so huge it’s almost beyond imagination. But I couldn’t do anything immediately. First, I had to complete an orientation which was required for all new employees and volunteers. Only after that did I get an access badge. Time was also lost sorting out different procedures and protocols which I thought had already been taken care of in The Netherlands. Okay, maybe that’s to be expected but it distracted initially from my purpose.”

Part of the orientation was for Louwes to gain an understanding of her surroundings, literally to figure out her way through all the different buildings and wings of the enormous complex. As well locally, to find a photo lab and where she could get a cup of coffee, which wasn’t that easy in the poor, minority neighborhood where the hospital was situated. And above all to understand the handling of the patients, how within their treatments she could incorporate her work, as it was not allowed to photograph the patients without their permission. The majority of the people in Kings County Hospital are in a six week outpatient treatment program. Some of these patients come from acute cases within the hospital and others literally walk in off the street.

“So in the daily practice there would be between 20-30 people who were there from nine in the morning until three in the afternoon. Because the patients began their six week programs at random, the groups constantly changed their composition. It seemed to me the majority of the men were shy, people who had fallen through the system, many with some sort of an addiction background. The women, often very strong types were almost all victims of violence, whether or not sexual, many with young children who they needed to care for. The most notable thing for which I wasn’t prepared was to be all of a sudden in a black, minority community. I was practically the only white person, and that was actually my biggest dilemma.”

“I was the odd man out, in every respect”

“I was the odd man out, in every respect. Photography is for these people a picture, proof for an identity card, or a large mural on the wall of an idyllic scene with palm trees. But it is not an art form, while I am an artist. The idea of art they did comprehend but in the form of therapy, like drama therapy for example. But I couldn’t sort myself into that kind of category. Around the hospital lived mostly poor African Americans and Latinos. I remained the intruder. I found this to be very complicated. I felt very humble and small, because of their pain, I was walking around there. For them I remained the white lady, which evokes distrust as well as respect. I went there the white European, to combat against the stigma of ‘poor black crazies’, by making photographs, which just produces more stigmas instead of less. For me that was a real struggle and it took awhile before I found a solution for both issues, in my head and in my work.”

The solution Louwes ultimately found was in the reversal of the image in the color negative. Black hair became white and skin blue, which applied to the skin of a colored person as well as a white, thereby the skin tone no longer played a role. She often photographed people from the back against a neutral background. With the photos, she made small sketch books which she carried around with her, to show and let the patients look and see her work. Slowly the contact deepened with a few of the patients.

“I participated with them throughout their whole program, in dancing, singing, ceramics, in group talk therapy, trying to get to know them, building up trust so that ultimately I could find the best moments. I worked with my large cameras as well as my iPhone to bring the surroundings thoroughly into view, 'mapping'. Everything got brought together, in a row, to clarify it for myself.”

“At one point I also began to photograph people lying down, as table tops. The models were in a fetus pose, a universal position. If something is going to work there is always a wait and see phase, but it begins with one person with whom you create contact, who trusts you and begins to work with you. Most of the time when that happens more will follow. But that’s with everything, I can only work if there is mutual trust and that takes time. There were also days when I didn’t make anything, nothing worked out. You know that in the beginning, that’s the way it goes, so I don’t get panicky about it anymore. When I left my room in the morning with my photography equipment slung over my shoulder, I felt like a fisherman going out for the day, you never know what you will come home with, you might not catch anything.”

Picture: Annaleen Louwes

“I never felt threatened or had a day where I said I’m stopping and going home. I had been at an artist in residency in Den Dolder, The Netherlands before so that helped, but this was still completely different. There were moments where you felt unsure, but that had more to do with the foreign language, a different culture that isn’t your own and in which you don’t know and understand the codes. I was the stranger who could participate and watch, but of course you don’t want to offend or interrupt in a therapy session. The actuality of the patient’s lives was almost inconceivable. No money, no job sometimes not even a roof over their head, living in homeless shelters, and some having children with them to care for. Then imagine getting yourself to the hospital every morning by nine for your treatment, which in itself is a huge accomplishment. How they did that, I don’t know, I can’t relate to that. Anymore than I can understand how you live knowing you probably will never break out of the cycle. And then not to mention the abuse that seldom stops, or the disorders, it’s no wonder that some relapse. Hearing the cry of distress ‘I only want to be happy’, from a woman suffering an intense attack made a deep impression on me. I often heard the phrase, 'think positive', just like other words, depressed, rain, fear, sunshine that came up in the therapy sessions giving meaning to the day. I found myself also becoming involved with words in my work.”

“In the end I photographed mostly men, the women were less willing. I began to make close up portraits for which people posed, some were staff, among whom many were also black. But that took awhile; I had to gain their trust. That always begins with one person, who becomes your ambassador and from there you can build out.”

“Sometimes there was a Code Orange, when someone went off the deep end and was a danger to themselves or the surroundings. Large men would manipulate the person into a corner so that an injection of a muscle relaxer could be administered. Not a pleasant sight but it was part of the reality. Those moments couldn’t be photographed, not only was that not allowed but your image would never be complete. Photography is complicated because you are so visible. The patients thought I was a bit crazy too but fun. Naturally I hope that there will be more artists that come after me. Continuity is very important; otherwise this kind of program won’t work. It is a different form of attention; you’re breaking through a system, with a lot of fixed roles and patterns, this applies to the hospital as well. I would like to see a composer come. The buildings are full of music as are the patients. I can see something in the King County Hospital Blues.”

Picture: Annaleen Louwes

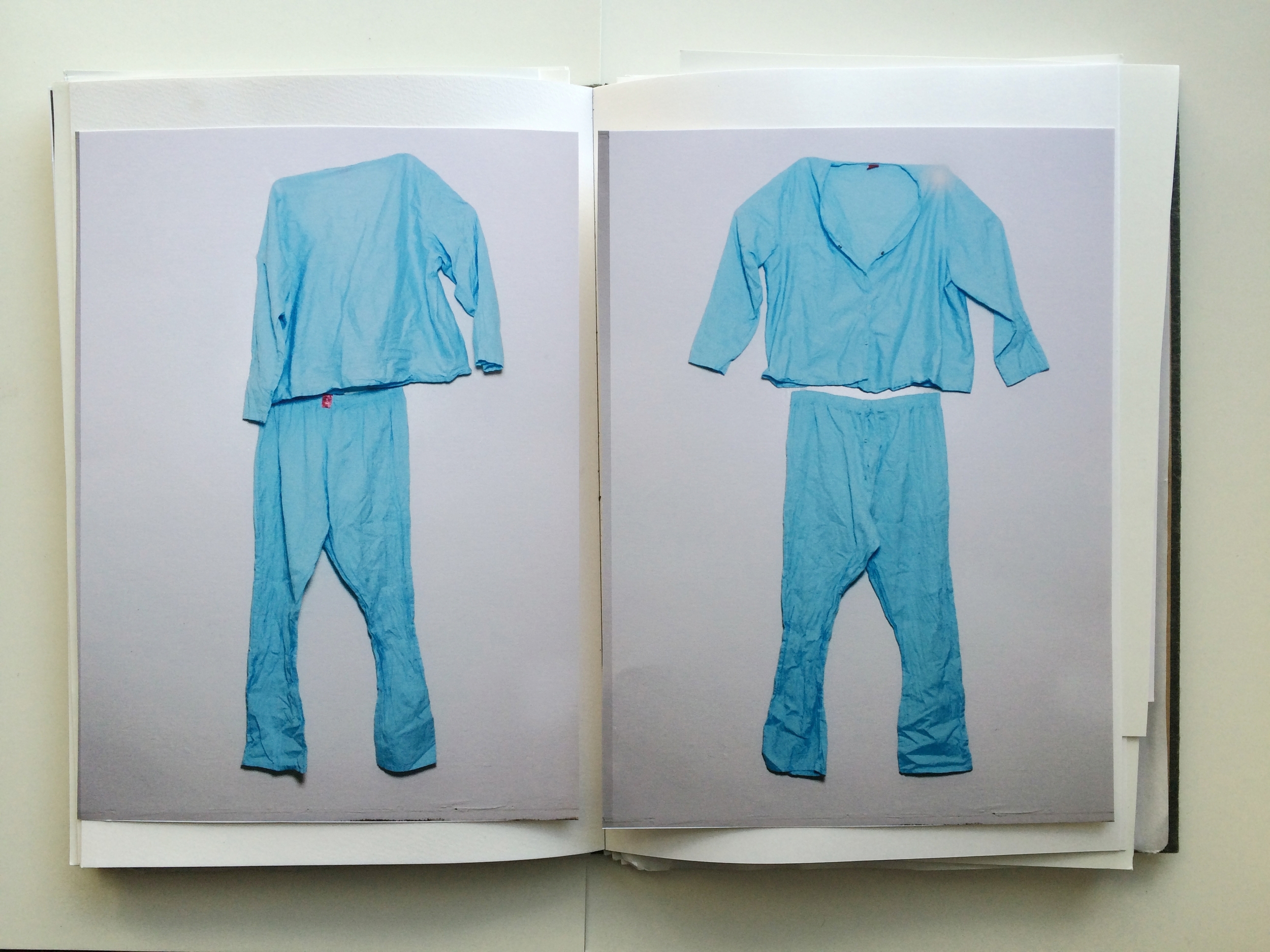

“All of a sudden halfway thru my stay, I found the denominator I had been searching for: Black and white and (some) kind of blue, referencing the pictures as negatives which I was working with, the photography itself, and on feeling blue. It even came back in the pajamas that the in-patients wore. What I liked is that the title refers to the photographs themselves without focusing on the craziness or the stigma. That’s what I ultimately wanted, I’m a photographer, what do I know about having a personality disorder. In the end it is only about my turmoil.”

“During my stay I continually hung things on the walls of my room in the hospital where I was working and living. The black-white-blue photos, photos from the surrounding area in daylight and in the evening, the table tops, therapy boards with text, and from the end the portraits. On the last day I had to take everything off the wall and lay it flat in my suitcase. That was a strange disintegration, which in its finality I found difficult. Now all the material lays in my studio here in Amsterdam, I have hung back up a few of the small items. Slowly everything is straightening out, and I’m getting a grasp again of things and am beginning to understand what I am going to do with it.”